Biodiversity

New discoveries on the spread of environmental toxins

It was previously believed that a family of chemicals which end up in the ocean, PFAS, remain there. But research from Stockholm University now indicates otherwise. Lab experiments reveal that these chemical substances can spread from water to air.

Subscribe to Extrakt newsletter!

Läs mer

Stay up to date! Get the knowledge, ideas and new solutions for a sustainable society.

Personal data is stored only for the mailing of Extrakt newsletters and information related to Extrakt’s operations. You can cancel the newsletter at any time, which means you will no longer receive any emails from us

“This completely upends how we’ve viewed these chemicals in environmental research,” says Jana Johansson, researcher at the Department of Environmental Science at Stockholm University.

She and her colleagues have conducted studies showing that substances whose final destination was thought to be the ocean can be borne in the air as aerosols – tiny water droplets in the air. The formation of aerosols is a natural process that occurs when waves break, but it has not been known that environmental toxins can be transported in the droplets.

“The fact that these substances don’t remain in the ocean means that they spread faster than previously believed,” Johansson says.

She explains that transport pathways in the ocean that can take years, decades or even centuries go much faster in air. In the air, these toxic substances can spread far in just a few weeks, days or hours.

“You could say that what we have in the air is everywhere. If you absolutely have to release environmental toxins, the best option is for them to be retained in one place. Then you can avoid things like using contaminated soil for cultivation. If the toxins spread in the air and rain down on fields, they become harder to avoid.”

Do not break down in nature

PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, is a collective term for more than 4,700 synthetically produced substances with different properties. Common to all these substances is that they do not easily degrade, if they do so at all.

“We know very little about most PFAS because only a few have been researched,” Johansson says.

Different PFAS have different transport pathways in the environment and varying degrees of toxicity. Some are dispersed in the air while others are water soluble and thus spread through water. It is this latter group, known as perfluorinated alkyl acids (PFAA), which is the focus of Stockholm University’s researchers. It is already known that this type of PFAS, despite being water soluble, can travel through the air. The substances have been found in remote mountain lakes and have also been measured in air and rain.

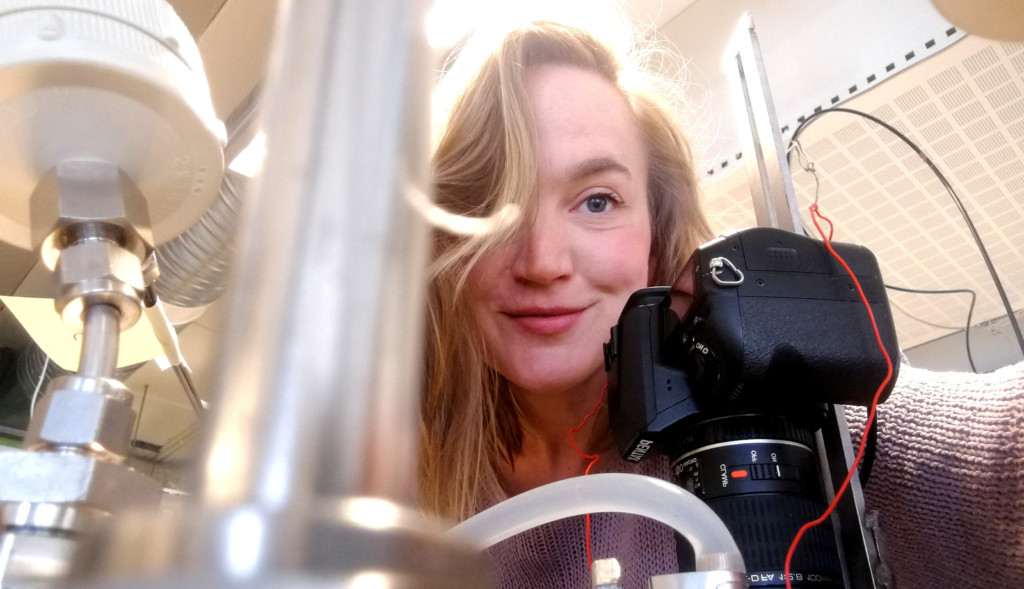

However, it is still unclear how these substances end up in the air. Jana Johansson and her colleagues hope to contribute a piece of the puzzle. In their lab at Stockholm University, they simulated waves breaking in a water-filled chamber and then took samples of the aerosols. Through this method, they observed that the chemical substances accompany the droplets into the air.

In a new, as-yet unpublished study, the researchers also conducted field studies of this water-to-air transfer phenomenon. Samples were taken off Norway’s northern coast, and the results revealed that aerosols with high levels of PFAS also had high levels of salt, which according to the researchers’ analysis indicates that they may come from the sea.

The researchers also took samples in southern Norway. There, in addition to aerosols containing salt, they also found droplets that did not contain high salinity levels yet contained high levels of PFAS. These chemicals probably come from sources other than the sea, such as emissions from industry, Johansson says. Other theories also suggest that water-soluble PFAS could be formed in the atmosphere through the reconstitution of other types of PFAS.

A bleak outlook for the environment

The significance of the transfer from oceans on the total amount of PFAA in the air cannot be ascertained yet, but Johansson believes it is significant.

“It appears to be a very important source, but there’s a lot of uncertainty because we’re just starting to measure it,” she says.

If it turns out that a large amount of PFAA in the air actually comes from the oceans, this sends a bleak message from an environmental perspective.

“If it had come from direct emissions, we could have done something about it by reducing emissions,” she says. “But if it comes from the oceans, we can’t do that much. It’s not possible to remove these substances from the environment – instead, they will continue to spread from sea to air for a long time to come.”

Many of the PFAS found in the environment today were released before the turn of the millennium. Since then, the rules governing the use of chemical substances have been tightened. But some PFAS are still used in various manufacturing processes and in products like detergents, fire-fighting foams, paints, cosmetics and packaging.

Jana Johansson hopes that their research will help decision-makers determine which substances should be allowed.

“It’s frightening that we release chemical substances that don’t degrade but continue to circulate in nature without our knowing how toxic they are,” she says.

PFAS

PFAS is a collective term for more than 4,700 identified substances with varying properties and broad use throughout society. They are used in various manufacturing processes and in products like detergents, paints, cosmetics and packaging.

Common to all PFAS is that they do not easily degrade and some substances can have harmful effects, for humans and the environment alike. All PFAS substances are synthetically produced. They are not naturally occurring in the environment.

Source: Swedish Chemicals Agency

THE HEALTH RISKS OF PFAS

In the latest risk assessment of PFAS, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that the most sensitive negative effect on humans is the impact on the immune system through a lowered antibody response following vaccination. PFAS also affect fat metabolism in the body. Reproductive disorders and cancer, while still hypotheses, have been observed in animal experiments at high doses.